By HARSH V. PANT

LONDON — This year is ending with some troubling signs of future instability in Asia, as two of the most powerful states are increasingly at odds with each other.

China’s lack of support to India in the aftermath of the Mumbai terror attacks and its attempts to block approval of the U.S.-India civilian nuclear energy cooperation pact at the Nuclear Suppliers Group have reinforced perceptions in India that China will do everything possible to halt India’s emergence as a major regional and global player.

Tensions over the boundary between the two sides are escalating. A few months back, China opened another front by raising objections over an area previously thought to have been settled. It contested Indian control of a 2.1-sq.-km area known as the Finger Area, in the northernmost tip of the Indian state of Sikkim.

Despite occasional rhetorical flourishes about an India-China partnership, the reality of Sino-Indian relations is getting more complicated by the day as the two Asian giants continue their ascent in the global interstate hierarchy.

In 2003, when then Indian Prime Minister A.B. Vajpayee visited Beijing, a bilateral agreement was signed in which India recognized Tibet as part of the territory of China and pledged not to allow “anti-China” political activities in India.

China in turn acknowledged India’s 1975 annexation of the former monarchy of Sikkim by agreeing to open a trading post along the border with the former kingdom and, later, by rectifying its official maps to include Sikkim as part of India. Although this was hailed as a major breakthrough in Sino-Indian ties, Beijing did not issue a formal statement recognizing Sikkim as part of India.

Five years later, things appear murkier with each passing day. Last year Chinese forces destroyed some Indian army bunkers at the Sikkim-Bhutan-Tibet junction and, more recently, has threatened to undertake cross-border forays to destroy stone demarcations in the Finger Area.

The Indian government has informed Parliament that Chinese forces have stepped up regular cross-border activities over the past year. Most recently, Chinese soldiers encroached 15 kilometers into India at the Burste post in the Ladakh sector along the Sino-Indian Boundary and burned the Indian patrol base.

According to some estimates, intrusions by Chinese forces into Indian territory have escalated to 213 incidents, up from 170 reported last year. China persists in refusing to recognize the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh as part of India, as it lays claim to 90,000 square kilometers. Having solved most border disputes with other countries, China seems reluctant to move ahead with India. The entire 4,057-km, Sino-Indian frontier is in dispute. India and China are the only neighbors known not to be separated by a mutually defined Line of Control.

Sino-Indian boundary talks seem to go on endlessly and the momentum for the talks seems to have flagged. China has adopted shifting positions on the border issue, time and again enunciating new principles but not explaining them. This deliberate opacity amid the tendency to spring surprises is typical of Chinese negotiating tactics to keep the interlocutor in a perpetual state of uncertainty, even as the facade of negotiations continues.

The real problem, however, is that India has no real bargaining leverage vis-a-vis China and negotiations rarely succeed in the absence of leverage. India, moreover, is not making any serious effort to get any economic, diplomatic or military leverage vis-a-vis its neighborhood dragon.

India seems to have lost the battle over Tibet to China, despite the fact that Tibet constitutes China’s only truly fundamental vulnerability vis-a-vis India. India has failed to limit China’s military use of Tibet despite the implications for Indian security, even as Tibet has become a platform for the projection of Chinese military power.

Not only has China pumped in infrastructural investments in developing roads, railways, airfields, hydroelectric and geothermal stations, leading to a huge influx of Han Chinese to Tibet, it is also rapidly expanding logistic capabilities of its armed forces in Tibet.

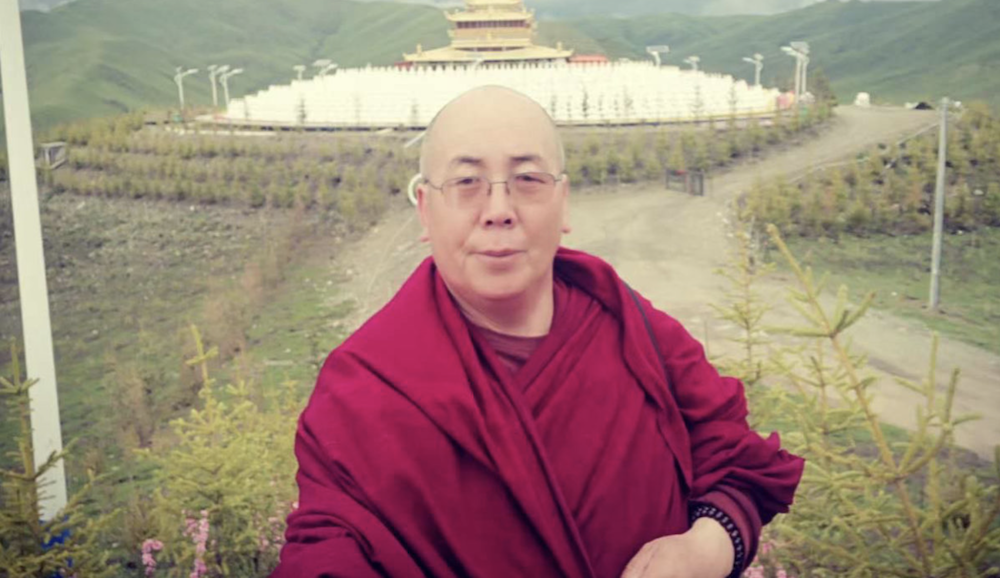

India’s tacit support to the Dalai Lama’s government in exile has failed to have much of an impact either on the international community. Even the Dalai Lama has given up his dream of an independent Tibet and is ready to talk to the Chinese, as he realizes that in a few years Tibet might become overwhelmed with the Han population and Tibetans themselves might become a minority.

Encouraged by the growing isolation of Tibetans, the Chinese government now seems to have little interest in a genuine dialogue with the Dalai Lama, who now concedes that his drive to secure autonomy for Tibet through negotiations with the Chinese government has failed, thus strengthening the hand of younger Tibetans who have long agitated for a more radical approach and who have demanded independence.

It is possible that recent turmoil among the Tibetans in China may be hardening Chinese perceptions vis-a-vis India. During the last visit of the Indian foreign minister to China, the Chinese government reportedly raised objections to the amount of media prominence given to the Dalai Lama and his supporters in India. The Indian government can do little about how the media treats the Tibetan cause, but the treatment will inevitably impact Sino-Indian ties. The Indian government has not been able to summon enough self-confidence even to allow peaceful protests by the Tibetans and to forcefully condemn Chinese physical assaults on the Tibetan minority and verbal assaults against the Dalai Lama.

China seems concerned about India’s pro-active foreign policy in recent years and its ability to play the same balance of power game that the Chinese are masters of. India’s growing closeness to the United States and the idea that democratic states in the Asia-Pacific such as India, Japan, Australia and the U.S. should work together to counter common threats is generating a strong negative reaction in Beijing.

Whatever the cause, the recent hardening of positions on both sides does not augur well for regional stability in Asia. Sino-Indian ties will likely determine the course of global politics in the coming years. The consequences of this development remain far from clear.

It is probably true that India-China relations will be one of the more significant factors that determine the course of human history in the 21st century. If present indications are anything to go by, human history is in for some tough times ahead.

Harsh V. Pant teaches at King’s College London and is the author of, most recently, “Contemporary Debates Indian Foreign and Security Policy.”