By Bhuchung K. Tsering

Tibetan Review, September 2005

As I write this, the Tibetan community in exile is preparing for yet another cycle of legislative elections (for the Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies), and for the post of the Kalon Tripa, our de facto Prime Minister.

In July-August, we went through our version of voter registration, producing our “Green Book” before the competent authority (in my case the board of the Capital Area Tibetan Association) so that they can endorse it.

The primary elections will be in September (for the Tibetan Parliament) and December (for the Kalon Tripa) while the main elections for both will be in March 2006. By September 2006 the election results should be out and the winners taking their posts.

While the Tibetans in Diaspora have had more than four decades of experience in one or another form of legislative elections, this will only be the second time that we will be having the popular elections for the Kalon Tripa. The Kalon Tripa is virtually the executive head of our Administration and had been appointed by His Holiness the Dalai Lama before the changes took place.

The forthcoming elections actually symbolize the development of Tibetan democracy. In the case of the Tibetan Parliament, members are elected from different sections of the community, three from the provinces, five from the religious lineages and one category from the nominated members. The composition and election system for the Tibetan Parliament have been made to make it as representative as possible of different sections of the Tibetan community. For example, although in exile, individuals belonging to U-Tsang province far outnumber those from Kham and Amdo, the provision of equal seats for the three provinces in the Parliament results in a strategic balance. Secondly, the system has been set up so that the Parliament symbolically represents the interest of Tibetan people as a whole, particularly those in Tibet who are not able to participate in this process.

However, there are challenges to the system. Since, each elected member is beholden to a specific section of the community, as opposed to a geographically defined constituency in exile, it has been a challenge to the parliamentarians not to be affected by regional and parochial partisanship.There are people who find fault with the system on technical grounds, too, saying that it goes against the one man, one vote rule. The plurality electoral system is applied for the ATPD elections with block vote rule being used. This means that each elector gets as many votes as there are seats to be filled in that particular category.There have been proposals for changing the system, including having a two tiered structure, in order to make the ATPD more relevant to the Tibetans in exile, who are in the forefront of this democratic experiment. Such proposals have not gone anywhere as yet.

In the case of the Kalon Tripa election, there is an attempt to apply the universal adult suffrage, including one man, one vote rule. In fact, the Charter i.e. our constitution specifically says that the Kalon Tripa election be held “without provincial, gender or sectarian discriminations” and that every eligible Tibetan above the age of 18 shall have the right to vote.

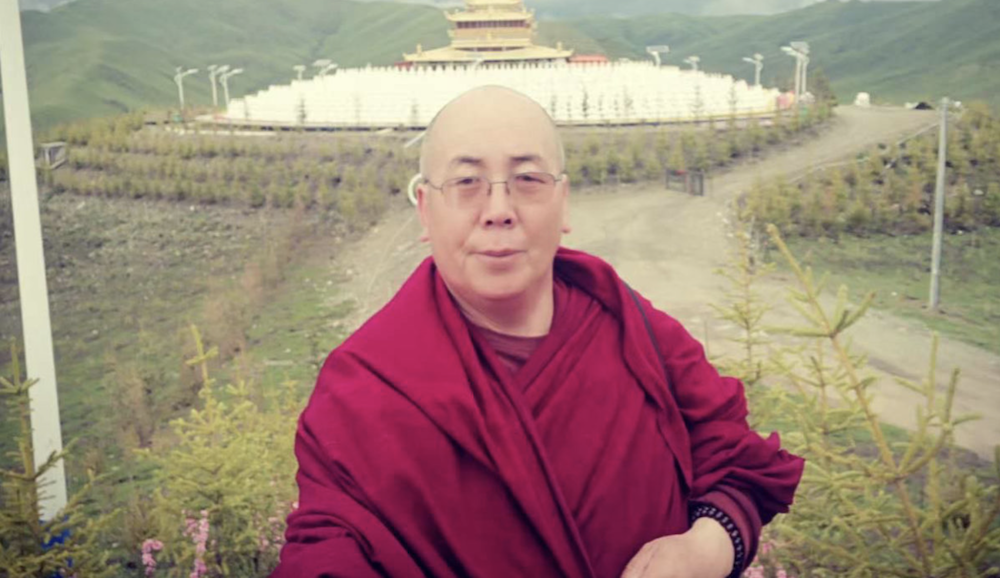

In the light of His Holiness the Dalai Lama divesting much of his authority to the Kalon Tripa, this position assumes much importance. At the time of writing this column, the question that is on everyone’s mind is whether the present Kalon Tripa, Prof. Samdhong Rinpoche, will “run” again. I am placing “run” in quotes because he was an unwilling candidate even for his first term. If he does consent to be a candidate again, there may not be doubt of him getting the second term. Although there are people who do not agree with some of his policies and find them idiosyncratic, the majority of Tibetans have come to appreciate his contribution. In fact, he may be the only Tibetan “political leader” (other than His Holiness) in exile to enjoy a visible recognition outside of the Tibetan community on his own merit.

We Tibetans are fond of saying that almost everything connected with us is Thunmong Mayinpa (“not common” or unique). While this statement may have to be taken with a pinch of salt on some of the issues, as far as our practice of democracy is concerned, it is certainly true. The democratic practice that has evolved within our community is something that may not have a parallel in any other society, the Greeks included. It is neither parliamentary nor presidential. It is neither one man one vote nor voting of a party. To add to the uniqueness, the election system applied to the Tibetan community in the Indian subcontinent is very much different from the one applied for Tibetans in Europe and the Americas. Also, unlike other democracies, our system evolved from top down, rather than bottom up.

In any case, the coming election period will be an interesting period. I hope we Tibetans can broaden our horizon through this experience. Whether as voters or as elected officials, we should do away with the narrow vision of a Trompai Belpa (a frog in the well) and learn to know that there is a wide world out there with which we are very much connected.

One way to achieve this is to disseminate as much information as possible about our elections to our own people and to the outside world. The Tibetan Election Commission could project itself through organizations like the International Foundation for Election System (www.ifes.org) so that the international community has a better understanding of our democratic practice. The Commission could set up a website (or expand its presence on www.tibet.net) devoted to the elections. The site could contain all the pertinent information that the Commission sends out to the community, including list of candidates, election schedule, etc.

Anyway, I am now ready to perform my civic duty.