By RICHARD N. OSTLING,

AP Religion Writer

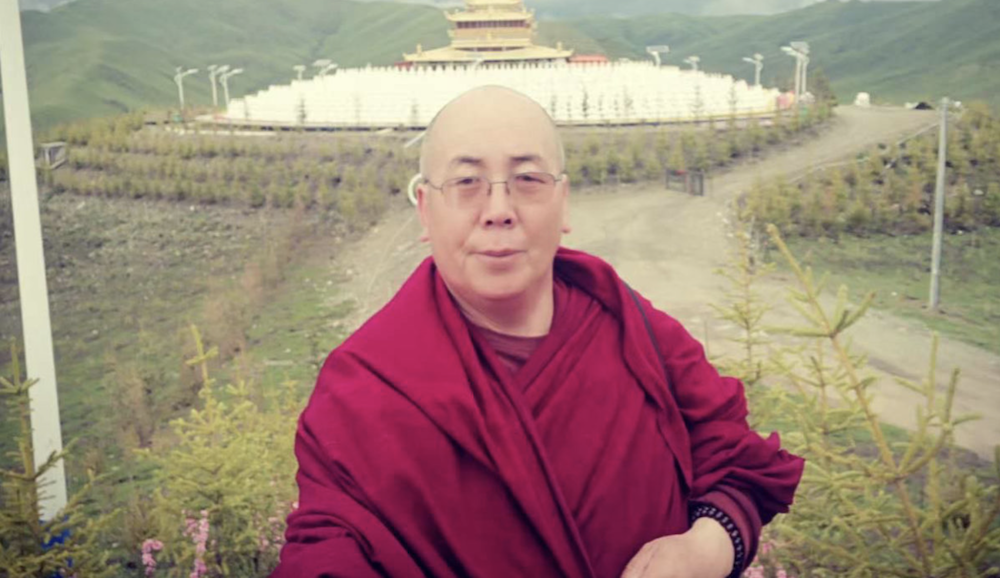

NEW YORK – The 14th Dalai Lama is simultaneously the exiled monarch of Tibet, a Nobel Peace Prize-winning statesman and Buddhism’s most renowned world leader — aspects that are all evident during his current U.S. tour.

But a private event, carrying out his religious role, may be the most significant moment in the India-based lama’s visit — a conference in the upstate New York community of Garrison for 300 leaders of local Buddhist centers in the Western Hemisphere.

This is apparently the biggest gathering of Buddhist teachers ever held in the United States. Only followers of the Dalai Lama’s own Tibetan form of the faith are invited, although some speakers will come from other traditions. The lama has previously encouraged smaller meetings for teachers representing all Buddhist branches, most recently in 2001.

Such get-togethers are rare because North American Buddhism is highly individualistic and decentralized, with less unity and nationwide cooperation than is found in Christianity, Judaism or Islam.

The Dalai Lama is asking the teachers to take stock after a period of notable New World expansion for all of Buddhism. The 1998 “Complete Guide to Buddhist America” listed over 1,000 dharma (“teaching”) centers in North America, more than double the total a decade earlier.

One survey puts U.S. Buddhists at 3 million to 4 million. Most are immigrants, their numbers swelled by the 1965 liberalization of U.S. immigration laws.

But an estimated 800,000 are native-born converts or “new Buddhists,” including such celebrities as movie actor Richard Gere, who helped plan the Sept. 22-23 Garrison meeting.

Such progress owes much to the magnetism of the 68-year-old Dalai Lama, who by Tibetan tradition was recognized at age 2 as an incarnation of Avalokiteshvar, the Buddha of Compassion, and the reincarnation of his deceased predecessor.

Tibetan Buddhism, known as Tantrism or Vajrayana (“the Diamond Vehicle,” denoting clarity of experience) is one of Buddhism’s three main branches. The others are Theravada (“the Way of the Elders”) and Mahayana (“the Greater Vehicle,” which includes Zen).

All three, and their many subgroups and spinoffs, are active in contemporary North America. In fact, this is “the first time in history you have all these diverse traditions in one place,” says historian Jan Willis, a Baptist-turned-Buddhist who will speak at Garrison. She tells her Wesleyan University students to speak of “Buddhisms,” plural, underscoring these varieties.

Though many branches live side by side, they mostly live apart, with the line between immigrants and “new Buddhists” particularly obvious. In the Tibetan branch, “new Buddhist” converts far outnumber ethnic immigrants, yet teachers imported from Asia overshadow U.S.-born leaders.

The agenda for Garrison covers a great deal of ground. Among the topics: challenges in teaching Tibetan Buddhism in the West; preserving the tradition; interfaith relations; responsibilities to society; and, promoting collaboration among Buddhists. The last topic is crucial for western Buddhism and especially for the Tibetans, says Helen Tworkov, editor of the independent Buddhist magazine Tricycle.

Tibet’s strong sectarian divisions naturally spill over to the West, Tworkov says, and “if they do not acknowledge it’s here, it will be hard to get beyond it.”

The Dalai Lama doesn’t hold the power of, say, the pope, and he actually leads only one of Tibet’s four major separate schools. But Tworkov says he enjoys a respect among almost all Buddhists that puts him in a unique position to foster unity.

She also says that, because the traditional Tibetan Buddhist culture is under threat of extinction from the Chinese occupation that led to the Dalai Lama’s exile, Tibetan teachers tend to be conservative.

The faith faces major adjustments in North America. The heritage of authoritative, male teachers clashes with feminism and democracy, for example, and liberals are rankled that the Dalai Lama teaches against homosexual activity, in keeping with Buddhist tradition.

Years ago, the Tibetan branch was rocked by scandals involving such prominent leaders as Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, founder of Colorado’s Naropa University, who was accused of having sex with women students and died of alcoholism.

In a dramatic (and still disputed) exercise of unified action, 21 Western Buddhist teachers met the Dalai Lama in India in 1993 and issued an open letter that lamented various teachers’ “sexual misconduct with their students, abuse of alcohol and drugs, misappropriation of funds and misuse of power.” The group urged believers to confront teachers and publicize behavior that violates Buddhist teachings.

“People have come through the scandal period,” says historian Willis, and now it’s time to contemplate long-term challenges that could be raised at Garrison.

She’s particularly concerned about two of them, that westerners attracted by meditation both neglect the faith’s devotional and ritual aspects and have little interest in joining monasteries, which have always supplied Buddhism’s teachers.

Without these elements, she’s concerned the faith may grow only shallow roots in the West.